This article was originally published as part of the "Feminist by Design" issue of the APRIA journal. APRIA (ArtEZ Platform for Research Interventions of the Arts) is an online platform that curates a peer-reviewed journal and publishes high-impact essays, image and sound contributions that examine art and interventions of the arts in relation to science and society, and that encourage dialogue around themes that are critical and urgent to the futures that we will live in.

Abstract

For the greater part of the 2010s and after the election of Jair Bolsonaro as president in 2018, Brazilian social media became an increasingly fertile ground for the exercise of public violence associated with political campaigning, often marked by gender, sexuality, class and race. As political tension increased with the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic, Bolsonaro openly disregarded and mocked scientific advice and showed contempt for expressions of care and empathy, which was consistent with the anti-intellectualism and gender script of his public persona.

This article focuses on two episodes on Twitter and Instagram that illustrate varied forms of network engagement with instances of homophobic hate speech uttered by or attributed to Bolsonaro. On the one hand, we highlight how the amplification of homophobic speech as a political code was afforded by Twitter’s design and algorithmic architecture. On the other hand, Instagram and Twitter also afforded the mobilisation of varied publics by means of memetic images in defence of public health and of sexual diversity, and in opposition to Bolsonaro’s homophobia. In face of dehumanising acts and discourse, we interrogate the possibilities of feminist intersectional investments in digital media in times of adversity.

Introduction [1]

The dissemination of hate discourse against feminist, LGBTQ+, and other minorities on social media was key to the rise in public support for the election of Jair Bolsonaro in October 2018 as president of Brazil.[2] By the time he was elected and an anti-rights agenda was consolidated as the moral compass of his government, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube and particularly WhatsApp had already become fertile sites for hate speech and sensationalism, facilitating the spread of disinformation and political attacks. [3] Bolsonaro’s public displays of anti-intellectualism and homophobia reached yet another peak with the outbreak of Covid-19 just over one year into his term. These displays were in place of an articulate government response to the pandemic. He soon became notorious for his open disregard of scientific evidence and protocol, as well as for his contempt for expressions of care and empathy, which he mocked as signs of weakness of character. His homophobic outbursts were consistent with the gender script of his performance as a public persona as a macho bully.

This article addresses the role of hate speech and expressions of gender and sexual prejudice in Brazilian right-wing populist networks and campaigning on social media, which were arguably key to their electoral success in 2018. [4] We first discuss the tactical combination of populist rhetoric and digital communication that configures a peculiarly powerful political pedagogy that was once again exercised in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic. Then, after some methodological considerations, we go on to describe two Twitter and Instagram trends during that period that illustrate varied forms of network engagement with instances of homophobic hate speech uttered by or attributed to Bolsonaro, the Brazilian president.

Homophobia, hate speech, and violence and discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender expression are broad terms that refer to varied forms of prejudice. What is at stake in legal, linguistic, sociological and psychological approaches to hateful speech acts is their capacity to harm individuals, groups and society as a whole. [5] In this article, we delve into the contextual—as a rule, contested—meanings of public manifestations of homophobic hate speech, a constitutive component of contemporary right-wing populism in Brazil. We first highlight how the amplification of hate speech as a political language was facilitated by Twitter’s design and algorithmic architecture. Second, we point to the possibilities of alternative social media vernaculars and issue networks as a type of resistance against this form of online political violence. [6]

Digital Populism

In a recent article about the role of WhatsApp in Jair Bolsonaro’s success as a populist, Brazilian anthropologist Letícia Cesarino associates Bolsonaro’s investment in social media and neglect of traditional channels of political debate with the cultivation of his image as a political outsider. In doing so, he promoted himself as an anti-system alternative in times of crisis. [7] Cesarino revisits Victor Turner’s analysis of ritual to explain the (re)making of political identities on social media platforms. [8]

Just like in a ritual, digital engagement generates a liminal space that enables the dissolution of established identities and the emergence of new ones. Furthermore, social media profile design has afforded the online formation of identities that are, according to Cesarino, ‘both highly individualistic and highly relational. While platforms allow for only one, well-bounded individual profile at a time, every profile is continuously co-produced through feedback loops with other user profiles. If such networked engagement disappears, the online persona ceases to exist as such.’ [9]

However, for Cesarino, unlike in traditional rituals, digital rituality does not produce the reintegration of unmediated identities. On the one hand, the continuity within and the separation between liminal spaces created by algorithmic classification mechanisms favour the isolation of users in so-called ‘bubbles.’ On the other hand, the person is permanently suspended in the performative in-between of liminality, as in a ritual process that never reaches closure. This is, according to Cesarino, fertile ground for processes of radicalisation. Populists take advantage of this quality of social media: ‘Like populist politics itself, the current architecture of social media complicates and challenges previously-held assumptions about agency and individuality, spontaneity and manipulation, freedom and control.’ [10]

According to Brazilian linguist Daniel N. Silva, Bolsonaro’s kind of populism configures a ‘pragmatics of chaos,’ inciting the communicability of hate and fear through incendiary framing and dispersive effects. [11] The illusion of non-mediation afforded by social media and the creation of micro-publics by algorithmic segmentation have a central role in that form of political communication, allowing ‘the impression of politics being decoupled from its conventional (formal) register, old bureaucratic channels, and possibly its corrupt mechanisms, and being reassembled in intimate, “unmediated,” transparent channels.’ [12] As Cesarino pointed out, in a ‘liminal environment where language becomes highly mimetic and performative,’ the ambiguity, ready-made replicability and divorce from content sources of messages conveyed by digital media supports a memetic pedagogy whereby digital populists teach their followers to speak and act like them. [13]

That ‘pragmatics of chaos’ was further fuelled by conspiracy theories and disinformation tactics regarding the coronavirus pandemic. This global ‘infodemic’ on social media, as the World Health Organization called it, [14] in Brazil was capitalised on and arguably stimulated by the negationist attitude held by Bolsonaro and his entourage. [15] By either live-streaming [16] or speaking to crowds at a close distance, as he often does, Bolsonaro has actively opposed social distancing as a violation of ‘citizens’ rights to come and go,’ claiming that ‘Brazil’s economy can’t stop’ for what he called ‘a little flu.’ [17]

‘Now everything is about the pandemic!’ he complained at an official function held to mark the ‘reopening of tourism in Brazil,’ in November 2020. ‘This has to stop! I’m sorry for the dead. I’m sorry. But we’re all gonna die someday. Here everybody is gonna die. […] It is no use running away from this, running away from reality. [You] have to stop [acting as] um país de maricas [a country of sissies].’ After uttering ‘maricas,’ he lowered his tone of voice and, as if commenting on what he had just said, he added: ‘A full plate for the vultures back there,’ referring to members of the press in the back of the audience. He was marking his words as a renewed provocation to the critics of his well-known anti-homosexual prejudice. He added: ‘We have to face this [challenge] with open arms, face the fight.’ [18]

The term maricas evokes the stigma traditionally attached to the passive partner in male homosexual intercourse, a feminised attribute used to denote inferiority. However, as Michel Misse has argued, [19] this classification does not designate men as homosexual; instead, it evokes the stigma of male homosexuality metaphorically, revealing its gendered dimension. Rather than saying that the target of the insult is gay, it implies that he is ‘less of a man,’ more often as a moral judgement about signs of lack of will or cowardice than about unconventional gender expression. In his speech, Bolsonaro urges Brazilians to be men, not ‘sissies,’ meaning that they must be brave and face death ‘with open arms,’ as a manly sacrifice. Implicit in that appeal is the strong cultural association between male homosexuality and moral weakness. As a paradigm, the symbolism of male homosexuality as a betrayal of a ‘natural’ condition of superiority attributed to ‘real’ men operates as a reminder of male domination. Bolsonaro’s remark generated some engagement in response on social media.

Digital Engagement

The speech in question took place in November 2020, a period during which we monitored controversies about feminism and LGBTQ+ issues on Twitter. We collected data using a combined strategy: user-end immersive observation using an anonymised research profile and digital tools at the back end. The term maricas stood out distinctively in posts by Bolsonarista profiles we followed. We queried that term from November 12 to 28 using Netlytic, an API-based social media text and social network analyser. This tool records up to 1,000 posts per query every fifteen minutes. [20] After removing tweets in languages other than Portuguese, our dataset comprised a sample of 62,440 posts in which the term maricas was used. Within that sample, a social network analysis of metadata was conducted to obtain a Co-Retweet Network (Co-RTN) comprising 33,485 tweets (self-retweets excluded), in turn represented using graph visualisation software. [21]

A Co-RTN shows accounts in the sample whose posts were retweeted by at least two other accounts, displaying an affinity of interest among accounts that retweeted a post originated by a third account. It reveals what we may call a ‘listening’ network and the effective propagation of tweets by accounts other than the one that originated the posts. Retweeting patterns link contents and accounts that users deem debatable on their networks. Accounts that have posts retweeted by one same third account can be regarded as connected because both accounts are somehow ‘heard’ by one same account and are, therefore, part of the ‘bubble’ around the latter. As a scoping method, a Co-RTN is a more adequate way to highlight forms of mediation specific to political issue engagement, if compared to first-degree popularity metrics. As suggested by Richard Rogers, one must account for intensely connected identifiable actors of varied characteristics, positioning and ways of engagement to measure engagement with political issues on social media. [22]

On a further note on research methodology and ethics, all of our social media data collection, including user-end queries, ethnographic observation and access to metadata either facilitated by platform APIs or utilising scraping scripts involved digital objects—human or automated profiles, text, image files and URLs either posted or used in profile descriptions, reactions, linked profiles, etc.—that were not only defined as public as a matter of legal regulation (either by platform default or by a user’s deliberate choice), but whose creators also intended to make public to the largest extent possible. That is, online activity and behaviour that sought their own exposure, the amplification of their messages as actors in the public sphere.

Alignment

Adopting their leader’s lexicon, Bolsonaro supporters propagated a term over the networks that had been otherwise infrequent, which was adopted into right-wing Twitter jargon. Maricas was mostly featured in tweets in support of Bolsonaro in reference to the pandemic, but also, for example, to his negationist stand on environmental issues. In that vein, maricas entered the political vocabulary of the Twitter-sphere with a relatively small variety of meanings. Posts by self-acclaimed true Bolsonaristas in our dataset mobilised the semantics of male domination as inflammatory language to execrate political adversaries, including former allies and dissidents. In this case, the main meaning of maricas was ‘coward,’ in the context of accusations of disloyalty or treason. In a slightly different vein, Bolsonaristas also adopted the term to make broader statements about morality and politics. Maricas always worked as a derogatory name, the attribution of which performs an injurious offence, regardless of political alignment. Those pragmatics are as relevant as the tweet’s thematic content, bringing to the fore who posted it, who the post talked about and to whom it was addressed, enacting and renewing a classification of friends and enemies.

Conversely, however, maricas was also used in posts contesting either Bolsonaro’s negationism regarding the Covid-19 pandemic, in response to his own use of the term in the episode that initiated the trend, or to contest his posture, often mockingly, about other issues. In these cases, the term had broadly the same negative connotations as in Bolsonaro’s and his supporters’ (unified) voice. Still, some tweets questioned Bolsonaro’s use of the term, embedded in broader critiques of his government’s absurdities, in particular with regard to the pandemic. However, as far as the sample can show, a great majority of occurrences of maricas indicate an assimilation of the gendered metaphor that gives the term its meaning. The use of the term did not, per se, generate controversy, at least in our sample. Few, if any, questioned its homophobic, sexist connotation. To look for that sort of questioning, we needed to make queries outside this dataset (that is, in posts not as densely co-retweeted), or compare the use of similar terms, as we shall see in the following sections.

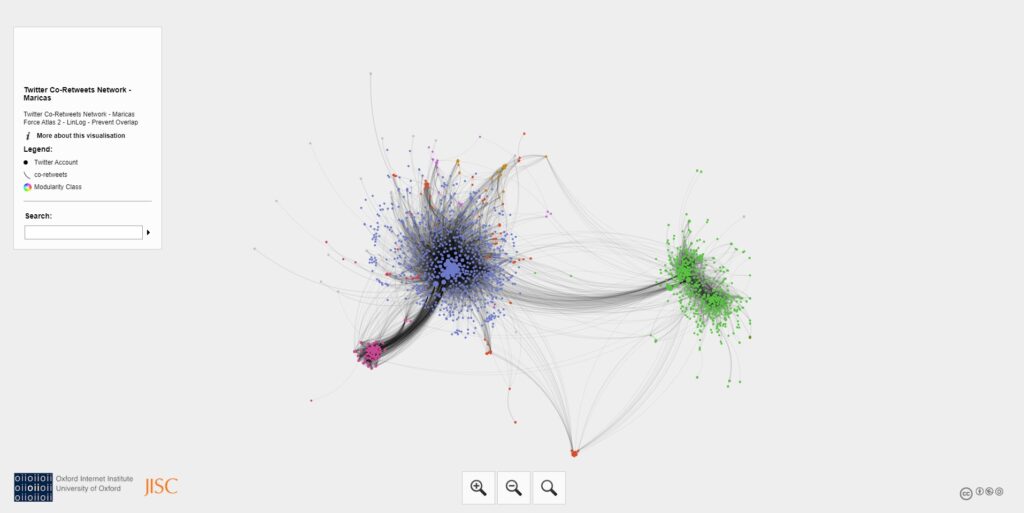

In the Co-RTN shown in the graph (figure 1), [23] four main clusters stand out: the largest one, in blue, highlights active Bolsonarista voices. Accounts belong, for instance, to the President’s third son, Eduardo Bolsonaro, a congressman who is very active on Twitter, [24] and to Olavo de Carvalho, the ultra-right-wing ideologue considered a guru of the Bolsonarista movement. In the blue cluster, we also find accounts not associated with public figures, but that are nonetheless very vocal in their support of Bolsonaro on Twitter. Conversely, the second-largest cluster, in green, which is slightly less compact, shows engagement with one post by former Secretary of State, General Carlos Alberto dos Santos Cruz’s account, a former ally now positioned as Bolsonaro’s adversary around different issues, and accounts that contest Bolsonaro’s negationism of the pandemic, among other intense criticisms. The pink cluster, the third largest of the four main groupings, well connected to the blue one but practically isolated from the green one, is another Bolsonarista network. The cluster includes Bolsonaro’s own account, as well as the account of Donald Trump, the former US president. Neither tweeted with the term maricas, but they were intensely spoken to in the sample.

Figure 1: Original graph created by Fabio Gouveia. ‘Maricas’ co-retweet network graph, 2021.

The blue cluster represents the largest Co-RTN in the maricas sample, with 809 accounts, out of a 1,646 total. The accounts most retweeted in that cluster belong to Bolsonarista accounts quite vocal on Twitter. However, these accounts are not associated with public figures. They used maricas with or without reference to its meaning in context, as a token of allegiance to their leadership and as a way to inflate the size of their following and push the term as a trending topic, inciting others to do the same. Much of their tweeting consists of the mere use of the term, as if they are just shouting the word out loud, or else combining it with either Bolsonarista iconography with no commentary or rants about real or imaginary political opponents.

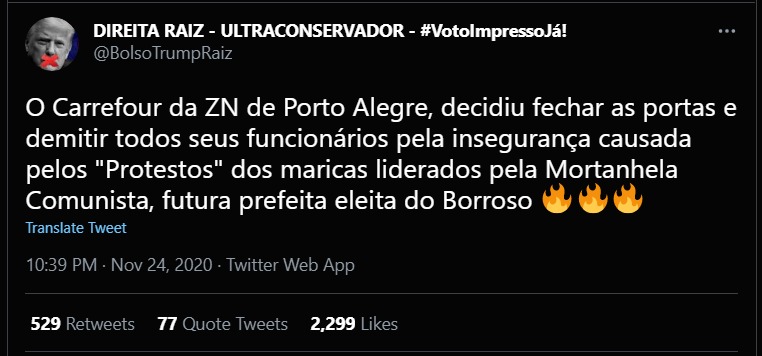

The vast majority of co-retweets of @BolsoTrumpRaiz—a profile identified as ‘ultra-conservative right-wing’ and the account retweeted the most in the blue cluster, as well as in the overall sample—correspond to a November 24 tweet (figure 2). That tweet expressed scorn for the protest movement sparked by the killing of a black customer by security guards at the entrance of a Carrefour supermarket in the city of Porto Alegre, a southern Brazilian state capital and metropolitan area. With an abundance of crude neologisms, innuendo and double-meaning, one single tweet serves the multiple purpose of accusing the black rights movement of reverse racism, while deprecating Bolsonaro’s political opponents. Other posts include attacks against the mainstream media and campaigning for Bolsonaro’s re-election.

Figure 2: @BolsoTrumRaiz tweet. The tweet lambasts Carrefour for closing due to protests against the killing of a black man by security guards and calls the protestors ‘maricas.’

As mentioned above, congressman Eduardo Bolsonaro tweets profusely. His account @BolsonaroSP stands out as another relevant exponent in the blue cluster, reflecting the congressman’s standing among Bolsonaristas on social media. Just like his father’s, his Twitter account is not only heard but is also spoken to significantly. His only post with the term maricas, tweeted on November 13 (figure 3), repurposes video footage, presumably from the time of the Brazilian military dictatorship (1964-1985), [25] of new recruits being introduced to the hardships of military training by an army officer. His text explanation refers to the gender script in his father’s message three days earlier, presenting military training as a ‘marica antidote, that is making men be men.’

Figure 3: @BolsonaroSP tweet. Tweet by Eduardo Bolsonaro, a congressman and son of Jair Bolsonaro. The tweet is his only mention of the term ‘maricas’ and shows repurposed video footage from the Brazilian dictatorship, calling military training a ‘marica antidote.’

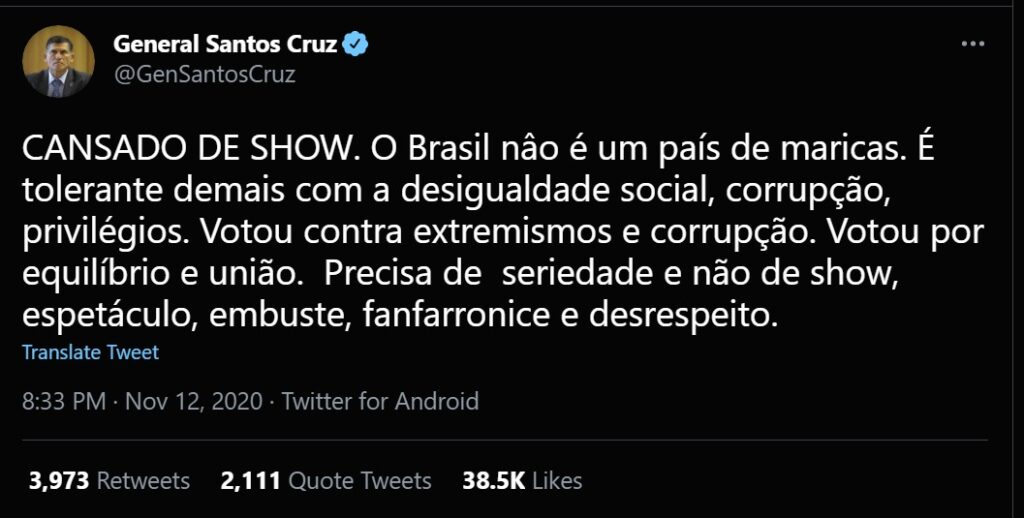

The term maricas was also adopted by Bolsonaristas to attack former allies whom they came to see as disloyal to the president. Among these ardent followers, any form of criticism is seen as a form of treason. General Carlos Alberto dos Santos Cruz is an army officer who was retired by the Bolsonaro government in 2019 after a message was attributed to him criticising Bolsonaro and his sons. The message circulated on social media and was later identified as fake. [26] Santos Cruz’s account, @GenSantosCruz, is the most retweeted exponent in the green cluster and the fourth in the whole sample. It is densely linked to 559 other accounts. Profiles in its network are connected by tweets more critical of Bolsonaro and his government.

Like Eduardo Bolsonaro’s, the General’s account also stands out for the number of mentions received (2,790), but in his case, this was mostly as the target of Bolsonarista hostility. A November 12 tweet by @GenSantosCruz (figure 4) reads: ‘TIRED OF [this] SHOW. Brazil is not a country of maricas. [Brazil] is too tolerant of social inequality, corruption, privilege. [Brazil] voted against extremism and corruption. [Brazil] voted for balance and unity. [The country] needs serenity and not a show, spectacle, hoax, bragging and disrespect.’ Responses include retweets in support of his statement. However, others raise their tone and call him maricas.

Figure 4: @GenSantosCruz tweet. Translation: ‘TIRED OF [this] SHOW. Brazil is not a country of maricas. [Brazil] is too tolerant of social inequality, corruption, privilege. [Brazil] voted against extremism and corruption. [Brazil] voted for balance and unity. [The country] needs serenity and not a show, spectacle, hoax, bragging and disrespect.’

Back at Bolsonaro: Contesting Negationism

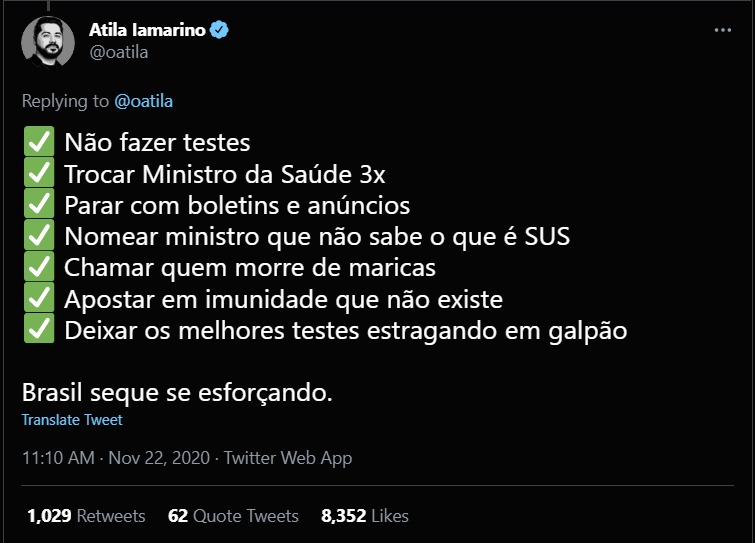

The green cluster also groups tweets that use the maricas episode to comment, with outraged irony, on Bolsonaro’s character and track record. In other tweets grouped on the green cluster, Bolsonaro is reproached for calling his fellow citizens maricas in the context of a broader critique of his genocidal handling of the new coronavirus pandemic. The biologist Atila Iamarino became a go-to expert on the pandemic; he was popular on social media and frequently interviewed by mainstream news media. His account has a certain prominence in the green cluster as the tenth-most co-retweeted in reference to two tweets that mention the term. His presence on the network is intense: those two posts were retweeted 1,011 times and @oatila was mentioned 300 times, showing that his voice was echoed and he was spoken to as well. A November 22 tweet by Iamarino’s account (figure 5) reads: ‘Do not take tests, [tick emoji]; Change Minister of Health 3 times, [tick emoji]; No more bulletins [or] announcements, [tick emoji]; Appoint a Health Minister who doesn’t know what SUS [National Public Health System], [tick emoji]; Call the dead sissies, [tick emoji]; Bet on non-existent immunity, [tick emoji]; Let the best tests spoil in a shed, [tick emoji]; Brazil keeps trying hard.’

Figure 5: Tweet by biologist @oatila. Translation: ‘Do not take tests, [tick emoji]; Change Minister of Health 3 times, [tick emoji]; No more bulletins [or] announcements, [tick emoji]; Appoint a Health Minister who doesn’t know what SUS [National Public Health System], [tick emoji]; Call the dead sissies, [tick emoji]; Bet on non-existent immunity, [tick emoji]; Let the best tests spoil in a shed, [tick emoji]; Brazil keeps trying hard.’

Yes, It Is a ‘Fag Thing’

As a precedent of the país de maricas episode, an earlier dispute involving Brazilian masculinities, homophobia and negationism of the Covid-19 pandemic took the form of a hashtag on Twitter and Instagram. It revolved around another homophobic expression attributed to Bolsonaro, ‘coisa de viado’ (‘a fag thing’). [27] The trend came up in our searches and personal timelines, although we were not monitoring Twitter trends on the platforms’ back-end via API at the time, as we later did. Therefore, our documentation of this episode is based on mainstream and alternative online media coverage and user-interface queries. The dispute is revealing about the combined performative effect of homophobic speech embedded in Bolsonarista discourse and its repercussions on social media.

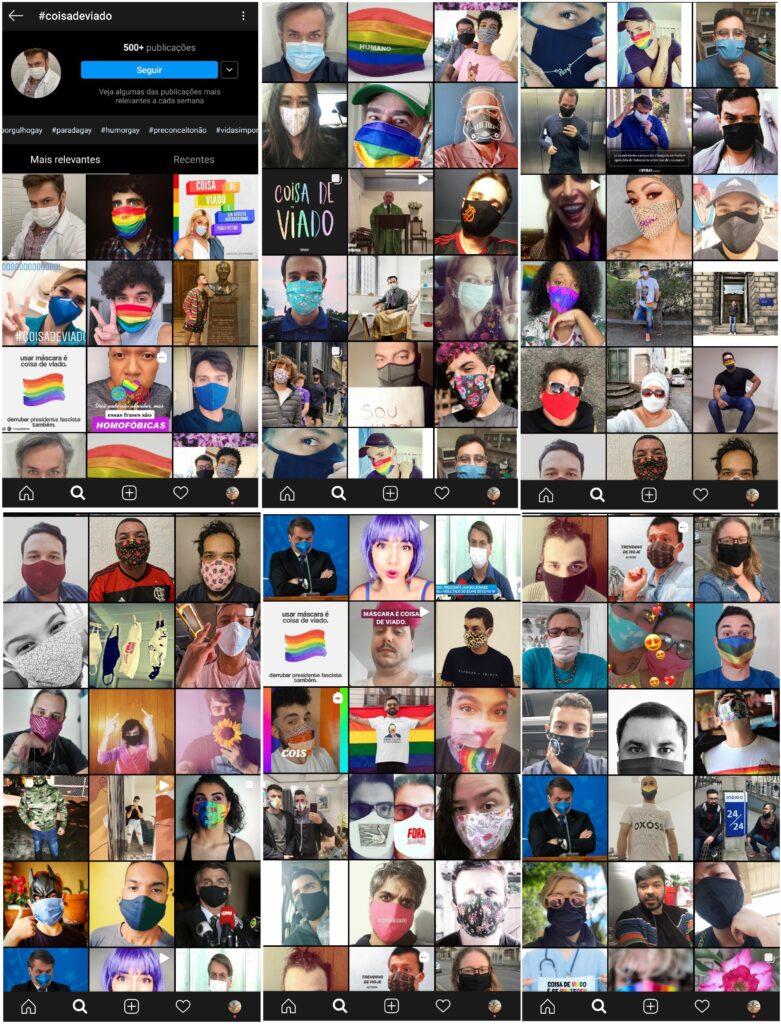

On July 7, 2020, the day when, after showing mild symptoms, Bolsonaro announced that he had tested positive for the coronavirus, Folha de São Paulo, one of the top mainstream newspapers in the country, ran a brief comment piece by senior columnist Mônica Bergamo about the president’s public insistence on disregarding the sanitary protocols recommended by scientists and health officials around the world in the context of the pandemic. [28] The most obvious expression of that attitude was his refusal to wear a face mask when he met with crowds because ‘[it was] a fag thing,’ which the article quoted him saying to visitors apprehensive about his attitude. The news that he had allegedly said those words in that context generated a movement in response, parodying the remark. Using the hashtag coisadeviado (‘afagthing’), all kinds of people posted selfies wearing masks in defence of public health, many of them with the rainbow colours, mobilising the symbol of gay pride as a protest against homophobia. Face masks thus became a symbol of resistance, ‘a fag thing’ that everyone was proud to do, say or wear.

Regardless of whether he had actually used that exact sentence on one occasion or another, reported by the news piece as hearsay, a wide network response added to its materiality. It was an everyday expression, the meaning of which is only situationally offensive, [29] that has also been actively reclaimed by queers. [30] But in Bolsonaro’s mouth, it synthesised the role of homophobia in his populist rhetoric and his active boycott of public health responses to the pandemic; in both cases, it was an appeal to his bases and a provocation to his political adversaries and critics. In response, the hashtag echoed the newspaper column’s denunciation of Bolsonaro’s active denial of the Covid-19 pandemic and of his homophobic remarks by appropriating ‘coisa de viado’ with a reverse meaning. The negative connotation expressed in the context of Bolsonaro’s alleged use of the term was replaced by a positive meaning adopted by his critics. The expression became part of a repertoire of ironies about Bolsonaro—as a reversal of his voice’s homophobic connotations and of the symbolism of the mask as unmanly. As a trending topic, the mask and its associated visuality signified care, responsibility, solidarity, dare to love, and the celebration of alternative masculinities. A front-end search for the #coisadeviado on Instagram on July 14, 2020, gave more than 500 valid results.

Men and women, particularly healthcare professionals, adopted the symbol and the hashtag in their posts (figure 6). Related themes included the government’s failure to respond to the pandemic consistently, its negationist agenda, Bolsonaro’s hypocrisy, other healthcare issues, etc. News media reported the phenomenon, added their comments and compiled posts, especially from Twitter, often mentioning fellow journalist Mônica Bergamo’s column as its origin. In addition to visual icons and photos, links to those news and comment pieces were also soon posted, reposted and replied to. In an ironic twist, some posts featured Bolsonaro with a mask on, shrugging.

Figure 6: @coisadeviado collage of Instagram screenshots.

In some Twitter posts, ‘coisa de viado’ still retains its pejorative connotation, highlighting its currency as an insult. A July 15 post shared a New York Times opinion piece that compared Bolsonaro to Donald Trump and quoted Brazilian YouTuber Felipe Neto (figure 7). The post’s text content celebrates Neto for that success. A July 16 reply marked with the hashtag (also figure 7) is an attack on both the author of the post and on Neto, casting doubt on their manhood: ‘You make a nice couple.’ Besides ironically suggesting that they are gay, the replier goes further by calling them ‘affected’ and ‘hysterical,’ two negative, feminising qualities, as well as ‘cheats.’

Figure 7: @augustodeAB & @clau_perl tweets. The replier uses negative, feminising words, such as ‘affected’ and ‘hysterical.’

The hashtag lost momentum over the following weeks, but the expression ‘a fag thing’ entered the catalogue of Bolsonaro absurdities and was adopted as part of a social media vernacular. It was transformed from a banal, mildly offensive homophobic remark to a symbol of resistance against toxic masculinities and obscurantism.

Social Media Affordabilities and Linguistic Nuance

The open hostility against the LGBTQ+ community by Bolsonaro and his entourage cannot be dissociated from the primary role of the anti-gender and anti-sexual rights agenda of his government. [31] Nor can it be dissociated from the surge in misogynist, racist and homo-lesbo-transphobic online threats and verbal attacks against candidates to public office in the 2020 municipal elections. [32] In connection with those two contexts, this article has interrogated the role of apparently milder—more ambiguous or more easily naturalised—forms of hate speech and expressions of gender and sexual prejudice that aid the assemblage and disassemblage of political identities performed by digital populism. [33] In materialising the status of sexual minorities as morally inferior, hate speech and prejudice produce forms of symbolic violence that reveal social inequalities and the workings of oppression. However, the affordabilities [34] of different platforms also aid the use of other genres and the creation of alternative codes as sites of resistance.

The maricas Co-RTN revealed the successful amplification of Bolsonaro’s message among a densely connected network of followers, or else competent users of that code, without much interference from outsiders who were neatly isolated from his camp. Conversely, Twitter, and to a greater extent Instagram, also facilitated a successful movement of contestation, delineated by the ‘coisa de viado’ trending topic, perhaps due in part to the higher currency of the key term ‘viado’ in Brazilian slang. Instagram’s privilege of visual content was particularly suited to the imagetic symbology mobilised by the #coisadeviado. This affordance allowed users to repurpose the two elements in dispute—mask and viado—as catchy visual icons with prosthetic potential. That is, as body extensions that enable the performance of identities less subject to language classifications and dissident from what is prescribed as ‘natural.’

Bolsonarista homophobia performs hegemonic masculinity as a constitutive aspect of a political identity and creates a hostile environment for feminists and sexual minorities. Diffuse and seemingly random provocations follow the logic of trolling. According to Herring et al., [35] there are two possible outcomes of systematic attempts to disrupt online spaces. One is the strengthening of an attacked group’s identity, especially through informal, witty, spontaneous forms of resistance. However, if a space no longer feels safe because of trolls, its members may feel forced to leave or stop engaging. Thus, trolling behaviour can lead to the deterioration of online environments.

More recently, Whitney Phillips associated the role of trolling behaviour with the current fascist turn on the internet and its electoral outcomes. [36] The mid and late 2000s saw an overlap between trolling subculture and a further-reaching internet culture that encompassed the expansion of social media. Popular culture absorbed the extreme irony and detached humour of both. Phillips highlights how the mainstreaming of those supposedly ‘fun’ and apparently harmless things has all along obscured their violent, undemocratic potential. In an earlier report, [37] we interpreted outsider trolling at lesbian Orkut [38] communities as semantic disputes around the issue of online security. For women and minorities in the pursuit of safer spaces, violence is very real, as is—we might add now—the harm produced by the blindness of privileged others. [39]

In the field of design, the term affordance designates the scope of relational properties that make a material instrument useful for human action. Social media affordances are often attributed a determining role in relation to the content and effects of the interactions that they mediate, by means of physical devices, user interfaces and digital networks. As a corrective to technological determinism in her feminist ‘critical’ approach to digital socialities, Jessalynn Keller seeks to encompass ‘not only the multiple qualities of social relationships facilitated through digital media but also the uneven power relationships that often shape these encounters [and] the structural inequalities exploited by the design of the internet.’ [40] She adopts the concept of ‘platform vernacular’ after Gibbs et al. [41] to highlight that online ‘communication genres develop not only from the affordances of particular social media platforms but also from the mediated practices and communicative habits of users.’ [42]

In her article on girls’ social media feminisms, Keller concludes that we ‘need to better understand the concept of affordance through a feminist lens, which can shed light on the gendered operations of power across various digital media platforms.’ [43] As she also points out—and which this article also painfully reveals—that task involves further engagement with anti-gender online vernaculars. As we make the final edits to this piece, the Bolsonaro government is trying to pass a law to further weaken the legal framework that enables some control on the spread of fake news and hate speech over the internet. [44] A finer understanding is needed of how the user interface design and algorithmic architecture of different platforms, old and new, afford the exercise of online violence. In this article, we have tried to emphasise that online hate violence is political and intersectional. Further research should also continue to address the complex articulation of gender, sexuality, class, race and political ideology, both as the roots of such hate and in activist responses to it, as well how platform design, artificial intelligence and internet regulation relate to that complexity, for better or worse.

Notes

[1] We thank our FIRN colleagues Namita Aavriti and Mariana Fossatti Cabrera, copy editor Shaun Lavelle, and two anonymous reviewers for their suggestions and feedback on this article. This research was made in partnership with the Association for Progressive Communications (APC) with support from the International Development Research Centre (IDRC, Canada) and the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES/Brazil).

[2] Sonia Corrêa and Isabela Kalil, ‘The Case of Brazil,’ in Anti-Gender politics in Latin America. Country Case Studies Summaries, ed. Sonia Corrêa, pp. 47-65 (Rio de Janeiro: ABIA, 2020), http://sxpolitics.org/GPAL/uploads/E-book-Resumos-completo.pdf

[3] Caio CV Machado, ‘WhatsApp's Influence in the Brazilian Election and How It Helped Jair Bolsonaro Win,’ Council on Foreign Relations 100, November 13, 2018, https://www.cfr.org/blog/whatsapps-influence-brazilian-election-and-how-it-helped-jair-bolsonaro-win; Cristina Tardáguila, Fabrício Benevenuto, and Pablo Ortellado, ‘Fake News Is Poisoning Brazilian Politics. WhatsApp Can Stop It,’ New York Times, October 17, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/17/opinion/brazil-election-fake-news-whatsapp.html Letícia Cesarino, ‘When Brazil’s Voters Became Followers,’ Anthropology News, September 14, 2020, DOI: 10.14506/AN.1497; Azmina Magazine and InternetLab, Monitora: Report on Online Political Violence on the Pages and Profiles of Candidates in the 2020 Municipal Elections (São Paulo, 2021), https://www.internetlab.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/5P_Relatorio_MonitorA-ENG.pdf.

[4] For a comprehensive, processual critical theory interpretation of Bolsonaro’s rise, see C. Rocha et al., The Bolsonaro Paradox (São Paulo: Springer & Friedrich Ebert Stiftung Brasil, 2021), https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-79653-2_4.

[5] For a thorough discussion of homophobic hate speech and its implications for Brazilian law, see Thiago Dias Oliva, ‘O Discurso de Ódio Contra as Minorias Sexuais e os Limites da Liberdade de Expressão no Brasil,’ M.A. thesis, University of São Paulo School of Law, 2014.

[6] We thank our FIRN colleagues Namita Aavriti and Mariana Fossatti Cabrera, copy editor Shaun Lavelle, and two anonymous reviewers for their suggestions and feedback on this article.

[7] Letícia Cesarino, ‘How Social Media Affords Populist Politics: Remarks on Liminality Based on the Brazilian Case,’ Trabalhos em Linguística Aplicada, 59 no. 1 (2020), DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/01031813686191620200410.

[8] Victor Turner, ‘Liminality and Communitas,’ in The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure, pp. 94-130 (Chicago: Aldine, 1969).

[9] Cesarino 2020, p. 412.

[10] Cesarino 2020, pp. 420-421.

[11] Daniel N. Silva, ‘The Pragmatics of Chaos: Parsing Bolsonaro’s Undemocratic Language,’ Trabalhos em Linguística Aplicada 59, no. 1 (2020), DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/01031813685291420200409.

[12] Silva 2020, p. 531.

[13] Cesarino 2020, p. 421.

[14] World Health Organization, joint statement by WHO, UN, UNICEF, UNDP, UNESCO, UNAIDS, ITU, UN Global Pulse, and IFRC: ‘Managing the COVID-19 Infodemic: Promoting Healthy Behaviours and Mitigating the Harm from Misinformation and Disinformation,’ September 23, 2020, https://www.who.int/news/item/23-09-2020-managing-the-covid-19-infodemic-promoting-healthy-behaviours-and-mitigating-the-harm-from-misinformation-and-disinformation.

[15] As we write this article and the death toll of the pandemic in Brazil reaches 600,000 reported losses, the testimonies of former Ministers of Health and other government officials before the Covid-19 Parliamentary Inquiry Commission (CPI) hold Bolsonaro responsible for promoting ‘early treatment’ with chloroquine well after that drug’s efficacy and safety were ruled out by scientific consensus, and for refusing to negotiate with pharmaceutical companies, delaying the acquisition of life-saving vaccines for months.

[16] As part of the strategy which eschews mainstream and traditional media channels in favour of social media communication tools, Bolsonaro has hosted weekly live transmissions on Facebook, in lieu of a presidential address to the nation. This was the case even before the Covid-19 pandemic and was unrelated to social distancing.

[17] France 24, ‘Brazil Economy “Can't Stop” for Coronavirus: Bolsonaro,’ March 30, 2020, https://www.france24.com/en/20200329-brazil-economy-can-t-stop-for-coronavirus-bolsonaro. Although long discredited, Bolsonaro reiterated his stance on social distancing at the 2021 UN General Assembly. See UN News, ‘Brazilian President Commits Country to Climate Neutrality by 2050,’ September 21, 2021, https://news.un.org/en/story/2021/09/1100472

[18] See the full transcript here (in Portuguese).

[19] Michel Misse, O Estigma do Passivo Sexual: Um Símbolo de Estigma no Discurso Cotidiano, 3rd (revised) ed. (Rio de Janeiro: Booklink: NECVU/IFCS/UFRJ: LeMetro/IFCS/UFRJ, 2007).

[20] As noted by Netlytics developers, Twitter's search service, and by extension its search API, does not guarantee a thorough collection of tweets. Not all tweets will be indexed or made available via the search interface. https://netlytic.org/home/?page_id=10834

[21] Analysis conducted by Fabio Gouveia. See Ray R. Larson, ‘Bibliometrics of the World Wide Web: An Exploratory Analysis of the Intellectual Structure of Cyberspace,’ Proceedings of ASIS96, pp. 71-78 (1996), http://sherlock.berkeley.edu/asis96/asis96.html; Fabio Castro Gouveia, ‘Acoplamento de Retuítes: Um Estudo Exploratório Sobre a Facada em Bolsonaro,’ Colóquio de Análise de Redes Aplicada. ISEG (Lisbon University, July 11-12, 2019), http://157.86.228.6/index.php/coloquioanaliseredes/cara2019/paper/view/537

[22] Richard Rogers, ‘Otherwise Engaged: Social Media from Vanity Metrics to Critical Analytics,’ International Journal of Communication 12 (2018): pp. 450-472, https://pure.uva.nl/ws/files/22792936/Rogers_IJOC_6407_30088_3_PB.pdf

[23] Interactive version available here.

[24] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eduardo_Bolsonaro

[25] Bolsonaro often boasts his revisionist view of the military regime, which contradicts the broad democratic consensus that has been constructed over the past 35 years in Brazil. Besides a glorification of militarism and his justification of torture and the suspension of legal guarantees, Bolsonaristas hold a nostalgic view of the discipline, prosperity and morals that they attribute to that period. A new military coup headed by Bolsonaro is an open possibility as a last resource against his enemies.

[26] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carlos_Alberto_dos_Santos_Cruz

[27] In Brazilian Portuguese, viado is a derogatory term for male homosexual. Its homophone veado most frequently refers to ‘male deer,’ although both spellings are interchangeable. There isn’t a consensus about the etymology of the term. Associations are made with transviado (masc. sing. noun), misfit, aimless; with the 1942 Disney feature Bambi, known for its meek and delicate appearance; or with both.

[28] Mônica Bergamo, ‘Máscara é “Coisa de Viado”, Dizia Bolsonaro na Frente de Visitas,’ Folha de São Paulo, July 7, 2020, https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/colunas/monicabergamo/2020/07/mascara-e-coisa-de-v-dizia-bolsonaro-na-frente-de-visitas.shtml

[29] The semantic ambiguity of terms whose offensiveness is contextual raises the issue of local context and conventions in social media content moderation: how can the actual meaning of a post be assessed based only on its terminology?

[30] An example of a non-derogatory use of terms such as viado is its inverted meaning as a prevalent stylistic feature of Gayspeak in many languages (and other subaltern sociolects, such as African-American English), whereby the stigma is contested by means of its reappropriation as a symbol of intimacy and solidarity among those who share it. In the context of joking relations, peers may call each other ‘fag’ not as an insult but to signal intense social proximity and affect.

[31] Corrêa and Kalil 2020.

[32] Azmina and InternetLab 2021.

[33] Cesarino 2020.

[34] Borrowed from the field of design, affordability in social media studies refers to the range of possibilities that a given platform’s interactive features offer to its users. We adopt the perspective that those features and their meanings are co-constructed and permanently repurposed by both users and designers. See notes 42 and 43 below.

[35] Susan Herring et al, ‘Searching for Safety Online: Managing “Trolling” in a Feminist Forum,’ The Information Society 18.5 (2002): pp. 371-384, https://doi.org/10.1080/01972240290108186

[36] Whitney Phillips, ‘It Wasn’t Just the Trolls: Early Internet Culture, “Fun,” and the Fires of Exclusionary Laughter,’ Social Media + Society 5, no. 3 (2019), https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305119849493

[37] Sonia Corrêa et al, ‘Internet Regulation and Sexual politics in Brazil,’ in EROTICS: Sex, Rights and the Internet. An Exploratory Research Study, Association for Progressive Communications, 2011, pp. 19-65, https://www.apc.org/sites/default/files/EROTICS_0.pdf

[38] Orkut was a social networking service operated by Google.

[39] Rocha et al. cite the maricas and coisa de viado episodes to illustrate the Bolsonaro’s capacity ‘to attribute an anti-system dimension to dominant social positions, especially, in Brazil’s case, regarding issues of gender and sexuality.’ By those discursive means, he gathered support in a constituency that is not far-right, ‘transforming hate speech into an acceptable and desirable rhetoric of political incorrectness, and voicing feelings of anger, revolt, and marginalization.’ (2021, p.146).

[40] Jessalynn Keller, ‘“Oh, She’s a Tumblr Feminist”: Exploring the Platform Vernacular of Girls’ Social Media Feminisms,’ Social Media + Society (2019), pp. 1-11, p. 2, DOI: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/2056305119867442

[41] Martin Gibbs, James Meese, Michael Arnold, Bjorn Nansen & Marcus Cartera, ‘#Funeral and Instagram: Death, Social Media and Platform Vernacular,’ Information, Communication & Society 18, pp. 255-268, DOI: 10.1080/1369118X.2014.987152

[42] Keller 2019, p. 4.

[43] Keller 2019, p. 8.

[44] Beatriz Gurgel & Guilherme Venagliada, ‘Após MP Devolvida, Bolsonaro Envia Projeto para Alterar Marco Civil da Internet,’ CNN Brasil, September 20, 2021, https://www.cnnbrasil.com.br/politica/apos-mp-devolvida-bolsonaro-envia-projeto-para-alterar-marco-civil-da-internet/