Last week I wrote about how we define the internet. This week, some thoughts about its history and its trajectory: how it’s moving from the past into the future, and how the former might inform the latter.

What is the history of the internet?

The internet’s still very young in terms of human history. Our focus also tends to be upon its future, on what it means for the emerging digital society.

But the internet’s been around now long enough for us to write some history. It’s more than fifty years since the creation of the ARPANET, the US military programme that’s regarded as its dawning; almost forty since the ARPANET adopted TCP/IP, the internet’s core protocols; more than thirty since the birthing of the World Wide Web.

The internet’s trajectory over that time’s been one of rapid change. What started as a communications mode for geeks has become the planet’s most important communications medium. The history of how that happened matters not just from the point of view of history itself; it’s also crucial to understanding how the internet might evolve into the future, how it might be shaped, how it interacts and is likely to with other aspects of society, and even what might come ‘after the internet’.

A technological perspective

Ask any internet insider, at least any technologist, and they’ll likely see its history in terms of its technology and services (just as, in last week’s blog, I suggested that technology tends to define the internet).

Technologists tend to see it, initially, as a break from what preceded it: a shift from one (tele)communications technology to another – from PSTN to packet switching, from POTS (plain old telephone service) to PANS (pretty amazing new stuff), as it was jokingly described. Something like the shift from candle power to electric light, from horse power to the motor car.

The foundation story stemming from this tends to follow the technology and services that it’s enabled: from ARPANET to internet (for many, still, to ‘Internet’), via TCP/IP, the Web, the Internet of Things; from usenet and ftp (file transfer protocol) to the Web (again), the cloud and social media. It is a tale of growing technological sophistication and diversity of services.

There’s a strong sense of ‘progress’ – even ‘inevitable progress’ – in this view of how the internet’s evolved. Historians use the term ‘whiggish’ to describe visions of history such as this – ‘characterized by a view which holds that history follows a path of inevitable progression and improvement and which judges the past in light of the present,’ as a leading dictionary puts it. The COVID pandemic has, if anything, exacerbated this ‘whiggish’ equation of the internet with progress because of the way it has facilitated activities during lockdowns in ways that wouldn’t have been possible before.

What’s wrong with that perspective?

That vision of the internet as symbolising progress has been influential. The internet's undeniable success in altering the scope and extending possibilities in economic, social, political and cultural space, changing societies (and changing those that it’s touched most the most), implies for many that more internet and more sophisticated internet’s the right way forward.

And in many ways that vision’s valid, but it’s problematic because it’s also partial. It misses out what hasn’t worked, by concentrating on what has. It focuses on the impact of what’s new without looking hard enough at the impact on what’s old. And it looks too little at the relationship between the internet and everything around it.

A technological history of the internet might have been sufficient in its early days, when it was less important, but it’s insufficient now. A history of the internet today should be more than a history of its technology. It needs to focus, I'd say, on its users and on how its used; the interface between it and other aspects of economy, society and culture; the part it’s played and is now playing in the broad spectrum of human history; how it has intersected with and how it’s influenced other major trends in human development over the course of its half-century, from geopolitics to the environment.

Why does this matter?

This matters because the internet’s important. The digital transition of which it’s been a leading part is altering characteristics of human society and its potential opportunities and risks which we need to understand as fully as we can if we’re to shape them. From a policy perspective, it is the history of this transforming impact that matters most, not the history of the protocols and algorithms, the nuts and bolts, that have enabled it.

Different aspects of that transformation have important histories of their own which form part of that perspective.

Take ‘access’, for example. It’s not just the numbers of us having access that have changed over time, but the nature of that access (from terminal to handheld, fixed to mobile) and what’s required from us (in terms of money and resources); the scope of what’s delivered through it; its impact on the lives of individuals and on the social and economic inequalities that are central determinants of digital divides.

Or take governance and ownership and business. We need to chronicle and reflect upon the transition of the internet from something that was first and foremost North American to something that is global; that was once principally technology but is now largely commercial; that was once decentralised but in which economic and political power are increasingly concentrated in few business and geographic hands.

The history of internet comprises multiple dimensions such as these. Some are primarily digital in context, such as the emergence of e-commerce, the growth of cybercrime, the significance of gaming, the trajectory of social media and its usages from MySpace and Friends Reunited to Facebook, Twitter and beyond.

Others are primarily about the interface between the digital and the non-digital: the internet’s impact on information, mis/disinformation and the media, for instance; its interface with the environment or with the SDGs; the way it’s altered power structures between individuals, the state, commercial businesses and one another; its impact on the world of work; its interface with crises such as COVID.

A much more rounded history, in short.

And for the future?

This also matters for the future, particularly where our view of innovation is concerned.

When we look back at innovations that have been transformative we tend to emphasise their positives/successes rather than their negatives/failures, but understanding both’s important to inform thinking about the future, particularly if we aim to shape that future – to make technology serve human goals and not determine them.

What would be useful?

I’m wary of the notion that we should ‘learn’ from history because it’s often overstressed. Today’s circumstances (our context) differ from the past’s, and appeals to history often prioritise past thinking over present, conserving what was rather than adapting to what is. However, understanding how we got to where we are, and the trajectory of the paths we’re on, are both crucial to effective policy development and business plans.

Two thoughts to focus on, perhaps.

The first is trend. The trends revealed by data sets in areas of policy like access are often more revealing, and better indicators of policy prescriptions, than snapshot data of the moment.

The second's understanding of the distinctions between aspiration, expectation and real outcomes. Ever since the significance of the internet became apparent in the late 1990s, it’s fostered speculation, much of it optimistic, some pessimistic. Subsequent history has shown most of that speculation to be poorly founded. Looking at why can help improve the reliability of projections for the future.

Understanding the history of the internet, in short, can help us shape its future – but only if it’s a history of its impact as well as its technology. Impact assessment's the subject of this blog next week.

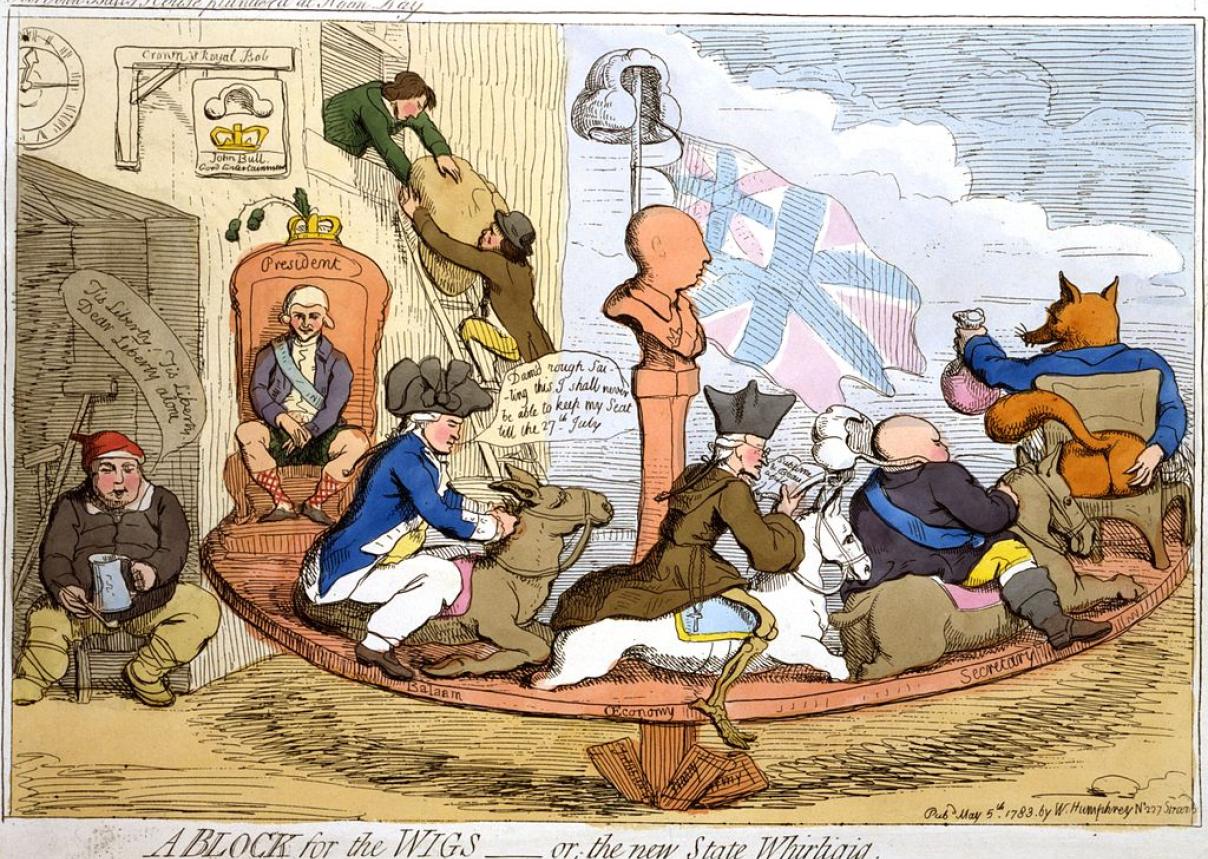

Image: "A block for the wigs", by James Gillray - Library of Congress, via Wikimedia Commons