I turned 65 years old last weekend: retirement age when I was young in Britain. Indulge me, please, in some nostalgia as I reflect on how information and communications have changed over that time (and not). I’ll end with lessons that I’ve learned about how to assess the changing ICT environment.

Some background

1955’s a long time back in many ways, but time’s flown fast for ICTs. Britain then, like everywhere, was a very analogue society. My own childhood was in a coalmining community in the neglected north-east part of England: much poorer, with fewer resources than the rest of Britain then (and still), let alone today’s kit-rich environment.

Digitalisation then was more science-fiction than anticipated fact, though there was fascination with future potential. One of the hit series of my television childhood was Tomorrow’s World, a weekly tech-fest that introduced Britons, among other things, to home computers (1967), mobile phones (1979) and compact discs (1981).

Now the nostalgia

Let’s not get ahead of myself. Here are some memories of my analogue-to-digital experience. It’s not unusual for people of my generation in my country. Younger readers, be amazed.

-

My father was a radar technician during the Second World War, working with technology that was then so unfamiliar that many people thought it was a death ray.

-

After that war was over, he made radio receivers. I had one in my childhood bedroom: a massive wooden box, full of valves (or vacuum tubes), because transistors weren’t invented when he made it. I got my first transistor radio in 1966. No streaming then on mobile phones.

-

We’d no television at home until I was five. When we did get one, it had a tiny screen, with an image made from 405 flickering black-and-white lines. There were just two channels, and they only broadcast in the evenings.

-

I remember my excitement when a library was built in Shiney Row, my village. Suddenly so many books, so many more than in the little travelling van I’d used to go to when it passed by once a week. That was my world wide web experience in childhood.

-

Almost no-one in the village had a private phone. The telephone was a call box at the end of the road, usually with a queue of people waiting. Coin-operated. When we did get a phone at home, a landline obviously, after six months on a waiting list, it was a party line – shared with another family, whose secrets we could hear if we picked up to make a call ourselves (and, obviously, vice versa). Calls beyond the local area had to go through the operator.

-

Music came on vinyl discs, though I also inherited the shellac 78rpm records that my (much older) sisters had collected (Buddy Holly, Little Richard). I bought one of my first LPs, aged 14, from the teenage Richard Branson, then trading cut-price records from the bedroom of his parent’s home (it was by Pink Floyd). CDs, now equally passé for many, did not arrive till early 1980s.

-

Social networks in those days were friendship groups that met in pubs not online chatrooms. We wrote letters then rather than emails, text messages or chats on WhatsApp. Correspondence with more distant friends was sporadic and much more carefully considered than it is today.

-

I wrote my PhD thesis on an electric typewriter. No word processing or home PCs back then: I had to draft and then retype, making corrections with the fluid known as tippex. (One of my first tasks in my first job, in 1979, was to review whether the typing pool should move from typewriters to word processing (using, of course, a mainframe not PCs).

-

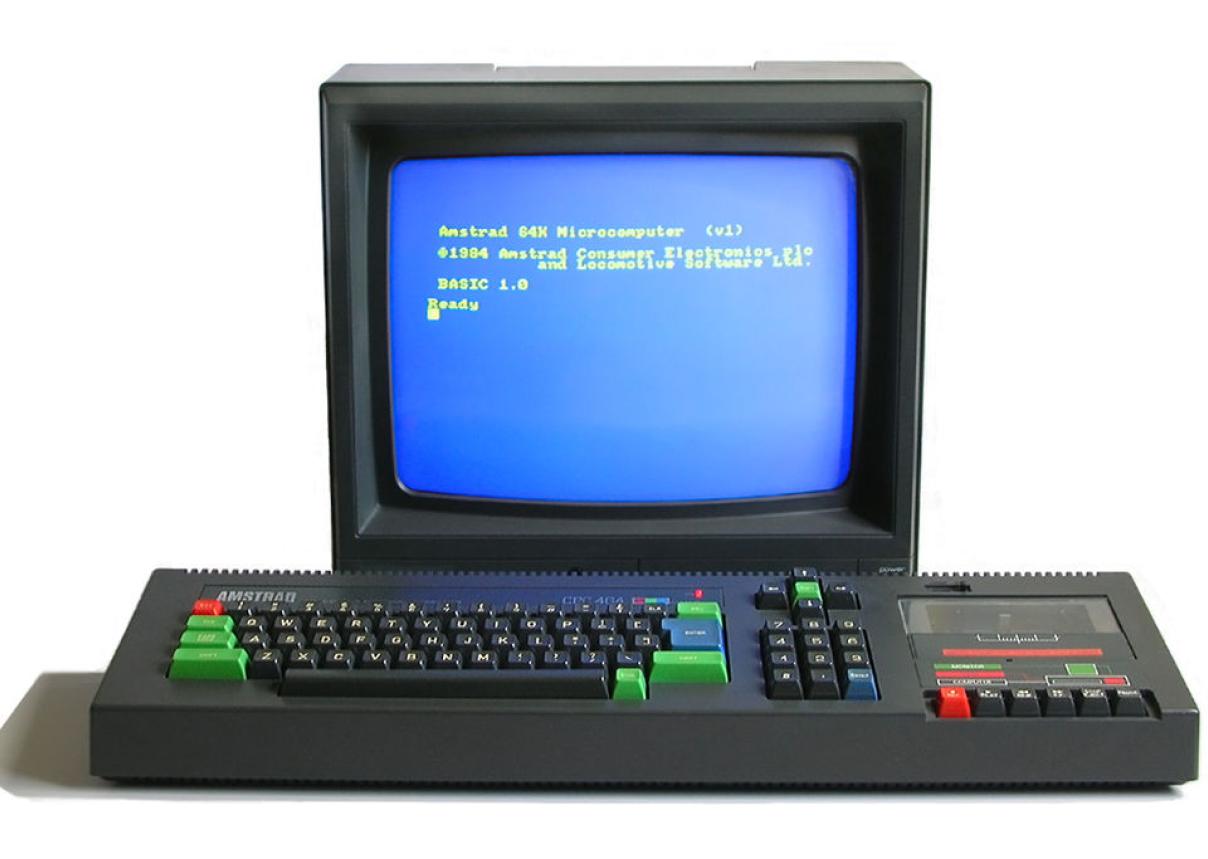

My first computer, in the early 1980s, was an Amstrad, which required two floppy disc drives – one for software, one for data files. Its operating system was proprietary, not even MS-DOS. No graphical user interfaces and the barest hint of RAM. At the time it seemed amazing.

-

I handled my first mobile phone when working for the trade union in Britain’s communications sector in the early 1990s. At union conferences I kept the union’s one and only (brick-sized) phone, hideously expensive and for urgent usage only. My own first mobile came along in 1995, to handle press calls on a book that I’d co-written.

-

I was using the internet by then as well, before the web went graphical, when modems buzzed and clicked their way to crawl-speed connectivity. The first specific use that I remember is a sad one: using file transfer protocol to find out information on the terminal disease with which my sister had been diagnosed.

What about the issues?

That’s personal nostalgia. But I’ve also worked within the sector for some thirty years, from 1989 in Britain, from 1995 around the world. I’ll pick four main themes from the many changes in that period.

From landline voice to mobile internet

In the early 1990s, the big issues that I dealt with (as head of research for the trade union in British communications) followed the reinvention of telecommunications – privatisation, liberalisation, and regulation.

Telecoms in Britain, like most other countries was a state-owned landline business in 1980. By 1990 it had become a competitive market, fixed and mobile, with an increasing range of ‘value-added services’. The infant internet’s become the biggest one of those.

The expansion of that business model (privatised, competitive) around the world preoccupied me for more than a decade, first in Britain, then in global development. That book that I co-wrote was about multistakeholder participation in the design and management of regulation (prescient, huh?).

From analogue to digital

That period also saw the start of mainstream digitalisation. In the 1980s British Telecom employed a quarter of a million people. In the 1990s, that figure halved as digitalisation swept away the need for many engineers and operating staff. Exchanges that had once employed forty or fifty people were down to occasional site visits by a lonely engineer.

Digitalisation’s since become the driving factor in the growing power and influence of ICTs. It’s why the ‘information’ society that was talked about in World Summits fifteen years ago is being supplanted now by ideas of a ‘digital society’. The internet, too, is being displaced at the core of digital by new waves of innovation that use it but reach out far beyond – device digitalisation that’s misleadingly called the ‘internet of things’; artificial intelligence; machine learning; algorithmic decision-making, data-driven governance and business.

The assumptions of the age of analogue are gone; we all assume the future’s digital. That’s driving politics and geopolitics as well as tech and human interaction.

From national to global

Old telecoms was national: British Telecom, France Telecom, Deutsche Telekom, Telkom South Africa. Today’s communications networks are international at least and often global. One-time state-owned telcos have long been privatised and internationalised, joined by one-time mobile start-ups and the more recent wave of internet-based platforms and data corporations.

Ironically, that globalisation’s also meant a new concentration of power – in the hands of powerful corporations, as is often noticed; but also in few countries, as less frequently observed. The concentration’s true in hardware – see current disputes about the role of Huawei in 5G networks – as well as software systems, platforms and data management.

It’s rooted in economies of scale that look increasingly to lie beyond the reach of those outside the current leading players. We hear much less these days of that old boast that “the next Google” could come from Africa or South America. Instead we find that two countries – China and the USA – account for 50% of global spending on the “internet of things”, 75% of the world market for public cloud computing and 90% of the market value of the world’s 70 largest digital platforms.

From sectoral to fundamental

The fourth’s to do with the shift of ICTs from the margins of economy, society and culture to their centre. People today think that they couldn’t live without things that we didn’t have when I was young. Digital technologies are now embedded in most aspects of government, economic and much social activity in most societies. Digital corporations have ambitions to dominate them in the future.

This is underway, not finished; and it’s unequal not more equal, as has been neatly demonstrated by the COVID crisis. Richer countries and richer parts of poorer countries have been able to shift a great deal of activity online. Digital alternatives have not been able to address the cause of the crisis itself, or to prevent large-scale economic dislocation, but they’ve been enough to mitigate that dislocation and they’ve been crucial to maintaining social interaction during lockdown.

Most of the systems we rely on now to make societies and economies function effectively, in most of our countries, are digital-dependent. They will become more so in all, but the gaps between degrees of digital engagement - and digital dependence - will remain.

What does all this nostalgia tell us?

The point of studying the past’s not to teach us what we should do now, for circumstances today are different from those back then. But it’s important to understand why we’ve got to where we are, with policies and regulations that seem less than perfect for the world we’re in. And we’d do better by remembering that the unexpected and the unanticipated often turn out more important than what is hoped or hyped.

I’ll make six points arising from reflections on the past that I’ve described. No space to go into more detail, but I think they’re all worth thinking over: from the past, through the present, to the future.

First, massive changes in information and communications are nothing new. They’ve been happening for decades. Their momentum is accelerating, though, which makes it more difficult (as well as more important) to predict their consequences or shape them in the public interest.

Second, this communications revolution is more complex than much of the discussion round it sees. It’s not just about technology and what technology can or could do for/to us, but about what people – those with power, those without – do with technology. It’s a mistake to look at the internet or at AI without looking at the context which (it’s thought) they might “transform”, asking who wants it transformed and why, and how they might pursue that.

Third, we may seek information and communicate today in different ways from how we did, but our reasons for informing and communicating aren’t all that different from what they were. They’re still about finding ways that work to do the things we really want to do: whether that’s wield power, make money, find love or have a laugh. The “transformation” that’s often observed’s to do with modalities more than with motivations.

Fourth, there’ll be big tech failures as well as tech successes. We tend to remember the latter and predict big future wins. Those gains are often going to be realised, but we should remember things that didn’t work. I’d cite, e.g., the low-earth satellites called GMPCS that were once touted as a global connectivity solution (and which lost big investments); the half-way house to mobile phones that was called telepoint; Google Glass; dozens upon dozens of poorly-designed, untested and ineffective platforms, apps and ICT4D initiatives.

Predicting what will work and what will not is difficult. Aspirations for digital transformation have often been overblown; and anxieties have oft been underplayed.

Fifth, there will be losers as well as winners from digitalisation. Inequality’s continued throughout a century of communications innovation, and will continue apace in the future. Each new technology is acquired and used unequally, first by those who can afford it and have the necessary skills and infrastructure, last by those who don’t. Economies of scope and scale in industry are concentrating economic power, and playing into geopolitics. Digitalisation doesn’t make power structures redundant; it gives them more potential than before.

Last, regulation has been critical to the recent history of communications. First, by injecting public interest goals into decisions that would otherwise be made on grounds that were entirely commercial – including data privacy and market competition, inclusion as well as innovation, human rights and the environment. Second, by establishing standards that have encouraged innovation and enabled it to become more effective. That experience has been poorly understood.

In conclusion

I’m glad I’ve lived through the communications revolutions I've described. I’m glad that I have access to more information, more music, more connections than I’d otherwise have had. I’m conscious, too, that some things have been lost. And I’m conscious that communications innovations have changed the ways we do things but haven’t changed the underlying character of economies, societies and cultures quite as much as people thought they would. They’ve changed human behaviour, not human nature.

We still live in a world beset by challenges that require a great deal more than the “transforming” power of ICTs. Geopolitics today resemble those that I grew up with in the 1950s and the 1960s. Inequalities of race and gender remain profound. There’s widespread and increasing polarisation in the politics of many countries; and there’s continued poverty in countries that are rich as well as those that aren’t. Carbon emissions and pollution are increasing. Conflict’s commonplace. We’re in the middle of pandemic. My children, their generation and the next need those problems to be dealt with more than they need a quicker way to download Marvel movies.

Image: By Bill Bertram - Own work, CC BY-SA 2.5, on Wikimedia Commons.

‘Inside the Digital Society’ will be taking its annual Northern summer / Southern winter break for the next six weeks. It will be back in early September with the big challenges facing internet governance and (I hope) with one or two surprises.