In 2018 the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) affirmed that the “surveillance of digital communications must be consistent with international human rights obligations” and in accordance with a “publicly accessible, clear, precise, comprehensive and nondiscriminatory” legal framework, without any arbitrary or unlawful interference with the right to privacy. UNGA called on states and business enterprises to protect and respect the right to privacy in the digital age in accordance with their respective responsibilities under international human rights law.

There is a stark difference between the normative statements expressed in UN resolutions and the realities experienced by individuals and communities on the ground across the globe. Individuals feel increasingly surveilled in multiple ways, including targeted, mass and lateral surveillance, with little knowledge on who is carrying out this surveillance or how. As noted by an activist at a recent consultation on the topic, “We feel like we are performing on a stage, with no knowledge of who the audience is.” The “curation” of these clandestine performances can often be credited to the surveillance technology industry, which behind the scenes is collecting, retaining, processing and exploiting data for governments, other companies, and other non-state actors willing to purchase a ticket.

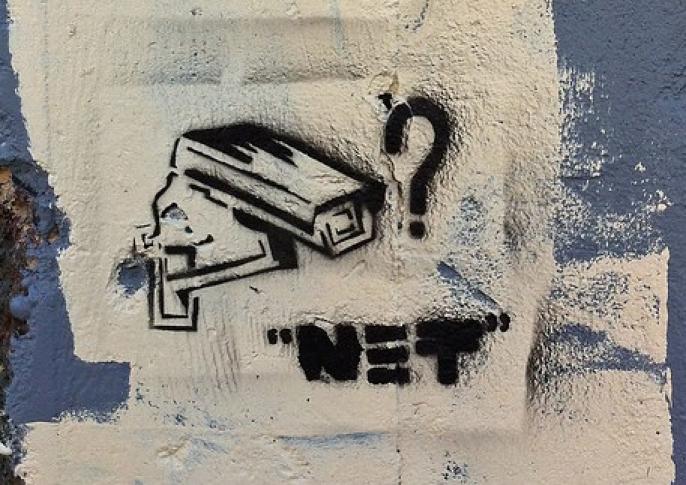

To a large extent, people are in the dark as to the different tools available to and being produced by state and non-state actors (especially private sector) that are used for surveillance purposes.

There is limited public information concerning the surveillance technology industry, which makes it difficult to hold either governments or private companies accountable for deploying surveillance technologies in ways that are inconsistent with international human rights law as well as domestic law. While surveillance technologies may have legitimate uses and be designed "neutrally", the reality is that they are deployed in ways that violate a range of human rights with impunity. Furthermore, as the Special Rapporteur has already recognised: "Surveillance exerts a disproportionate impact on the freedom of expression of a wide range of vulnerable groups, including racial, religious, ethnic, gender and sexual minorities, members of certain political parties, civil society, human rights defenders, professionals such as journalists, lawyers and trade unionists, victims of violence and abuse, and children."

The same can be said for surveillance technologies. Whether targets of government surveillance (like activists, human rights defenders, journalists whose communications and devices are intercepted) or subjects of lateral/social surveillance (like survivors of domestic violence who are targeted with spousal spyware and experience new forms of domestic violence through “internet of things” devices), persons who are in positions of vulnerability and marginalisation in society, including political dissidents, minority rights activists, persons living in conflict areas and women or persons of varying gender identity, tend to experience disproportionate effects from the deployment of surveillance technologies.

Due to the limitations on space, this submission focuses on emblematic cases and uses of surveillance technologies against individuals or civil society organisations, and the gendered impact of the deployment of surveillance technologies.