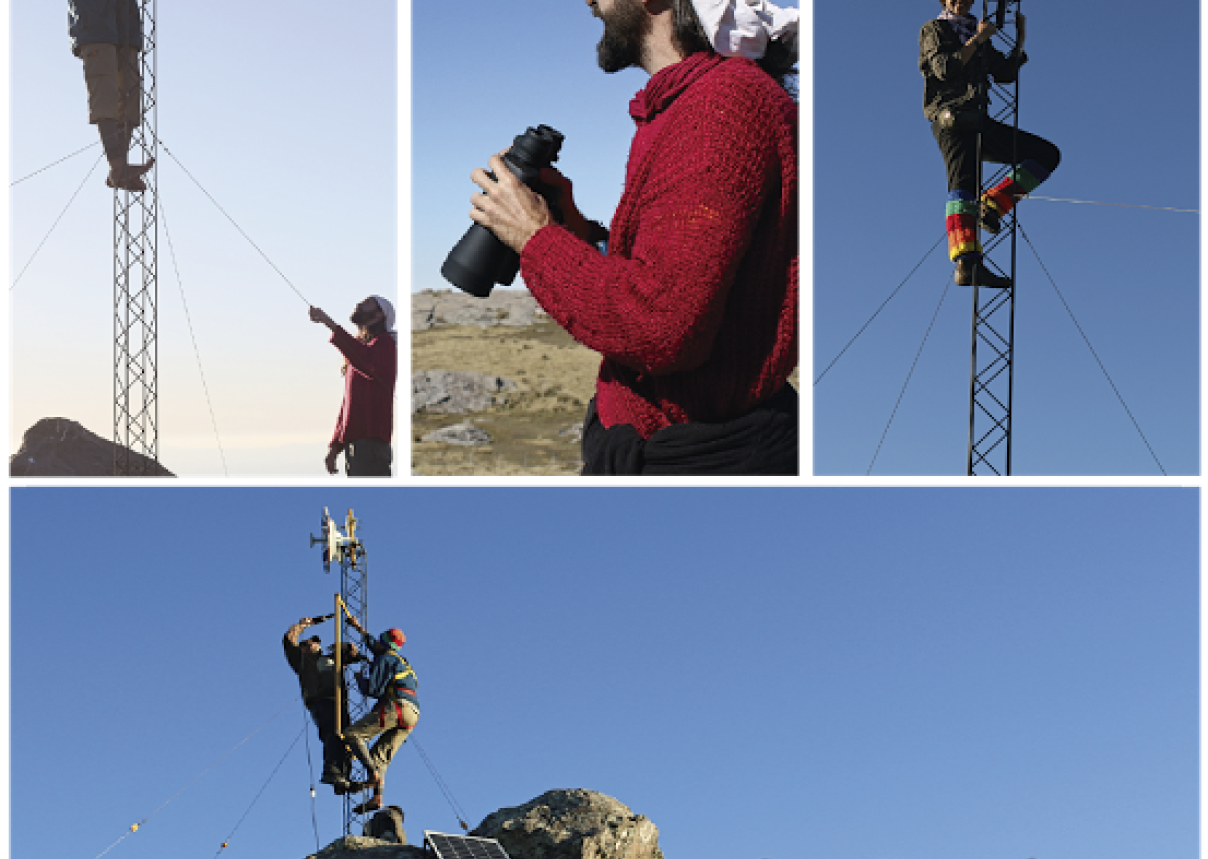

AlterMundi in action in Córdoba, Argentina. Photos: AlterMundiEach week David Souter comments on an important issue for APC members and others concerned about the Information Society. This week’s blog suggests a short history of ICTs in development.

AlterMundi in action in Córdoba, Argentina. Photos: AlterMundiEach week David Souter comments on an important issue for APC members and others concerned about the Information Society. This week’s blog suggests a short history of ICTs in development.

Two weeks ago I offered a short history of the Internet. This week I’ll follow up with thoughts on a short history of ICTs in development (ICT4D).

There are plenty of potential origins. Some would go back only as far as WSIS, a decade ago, but that’s too recent. Others, more realistically, to a spate of conferences and initiatives that sparked interest and excitement in the mid to late 90s, leading to a UN Task Force. Others again to the ITU’s Maitland Commission, which was set up in 1983 to investigate what we now call the digital divide. Or to UN investigations of ‘the application of computer technology for development’ in the early 70s. Or the first uses of computing in developing countries in the 50s. Even to the completion of global telecommunications networks at the turn of the 19th/20th centuries.

Myself, I’d date use of the term (‘ICT4D’) from the mid-90s. That’s when it began to figure in wider development debates.

As with my short history of the Internet, what follows is just my suggestion, intended to provoke reflection, based on personal experience. There are lots of other views. Here goes.

The decade after Maitland: from inquiry to indifference

I’ll start with the Maitland Commission in the mid-80s, long before the Internet played any part in thinking on development. It pointed out that telephone access in developing countries was confined to government, big business and the rich, with phone density rates in Africa as low as 0.1% of population. This was morally wrong, it said, and economically harmful to both North and South. It called for cross-subsidies to unlock the social and developmental value of the phone.

I’d say that Maitland raised the profile of the issue but it didn’t lead to major change. In the decade following, up to the mid-90s, development agencies were indifferent. They considered telecoms an elite product of little value to the poor, and left investment in it to the private sector. That investment came much more readily in Asia and Latin America than in Africa, where phone density rates barely increased.

From indifference to excitement, enthusiasm and expectation

The turn-round came in the mid-90s. New ICTs were making waves in developed countries: mobile phones, PCs, the early Web: smaller, cheaper, accessible, with the potential to add value locally and sectorally, to national economic development and small-scale local applications. A wave of enthusiasm for ICTs’ potential swept over parts of the development community, captivated by the thought that developing countries could use ICTs to ‘leapfrog’ a century of failures to deliver social and economic goals.

This vision was shared by enthusiasts in dozens of conferences and initiatives, sponsored by the UN, the World Bank, the European Union, the OECD, Northern development agencies, some Southern governments. Pilot projects proliferated. The Information Society seemed to be around the corner.

Looking back today, I see two strands in this enthusiasm. Some saw the Information Society as an observable phenomenon: a gradual, if rapid, process that could be watched and learnt from. Others saw it as an aspirational vision, a goal to be pursued through advocacy, infrastructure and dedicated strategies and programmes.

WSIS and its aftermath

This new enthusiasm reached a climax in the World Summit on the Information Society (2003-2005), when the ICT industry and ICT4D advocates joined to promote their new technologies as core solutions to developmental challenges. There was an evangelical zeal abroad at WSIS, which spread awareness and engagement, not least within developing country governments, many of which began to put together national ICT4D strategies. It looked like ICT4D had made it to the forefront of development.

But WSIS, I’d suggest, also marked a highpoint of enthusiasm.

Development agency awareness (and funding) turned away from ICT4D post-WSIS towards other priorities (the Millennium Development Goals, which barely mentioned ICTs and climate change). Development professionals outside ICT4D remained wary of technology-led ‘solutions’ to deep-seated, complex human, economic, social and environmental challenges they’d spent decades learning to understand and to address.

ICT4D failed to influence mainstream development thinking to the same degree that ICTs were changing economic and social structures in the years post-WSIS. In particular, it failed to make much mark on the Sustainable Development Goals that were eventually agreed in 2015.

Since WSIS: a decade of increasing impact and complexity

Which is not to say that ICT4D stood still. I’d point to two things which have fundamentally altered its parameters since WSIS.

The first’s mobility. The WSIS texts have lots to say about the Internet, almost nothing about mobile phones – but it’s mobile phones that have been the ICT of choice for developing country citizens, including the poor. Mobile phones that have been accessible and affordable, met people’s self-identified requirements, had significant impacts on their lives and livelihoods, provided the main platform for access to the Internet.

Their unexpected new pervasiveness has also changed the scope for ICT4D. Developmental change is being driven at least as much by the way people adopt and use their ICTs as it is by the strategies and programmes of governments and development agencies. Smart development actors have built on this by leveraging that usage, building on how people choose to use their phones in a process Richard Heeks dubbed ICT4D 2.0 .

We’ve acquired much more experience of ICTs within development, not just from pilot projects but more extensive programmes, implemented over longer periods. Successes, failures, and, in most cases, some of each.

E-government and e-commerce are becoming widespread in developing as well as in developed countries. People are making use of apps that were not intended for development to meet their personal developmental needs. ICTs are becoming part of development without necessarily being 4D.

From implementation towards information societies

So where do we go from here? We still have a dilemma, a paradigm gap in thinking about ICTs and development. The world community’s adopted its 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, but that underestimates the growing influence of ICTs on how that will play out. The ICT sector believes its goods and services have profound developmental value, but underestimates the human challenges and complexities that make development difficult.

The UN’s WSIS+10 review offers a new starting point – not so much because of what it said, but because it draws a line under WSIS itself. It’s cleared the way for some fresh thinking.

More important for development than that review was the systematic overview of ICT4D which the World Bank conducted in its World Development Report for 2016. That took a more mature view of ICT4D’s achievements and direction – looking at the evidence to date, recognising that achievements have been well below aspirations at the time of WSIS, exploring the challenges posed to development as well as the opportunities afforded by these new technologies.

That’s a good starting point for reflecting on the future, at sectoral and national level. A more evidence-based approach is, fortunately, now emerging, with more analysis, less rhetoric – a better mix between the information society as an observable phenomenon and as an aspirational vision. But it still needs to overcome two things: the hyper-optimism of many in the ICT community, and the scepticism of many in mainstream development.

Three challenges

I’ll end with three challenges emerging from this.

The first is realism. ICTs are changing our economies, societies and cultures, but they are not the only forces doing so. Development is difficult and complex. That’s why it takes so long. If ICT4D’s to be successful, it should seek to achieve what’s possible, not what’s ideal, recognising the hard challenges of people’s lives, the realities of power structures, the limitations of technology and the risks of inequality that are inherent in any innovation.

The second’s evidence. Too much of the literature of ICT4D has focused on hopes for what could happen in ideal circumstances, rather than understanding what’s happening in real ones. We’re now getting a much better and much bigger mass of evidence on ICT4D experience. The World Development Report made a good start at its analysis. Other research is beginning to show what has and what has not been achieved in different ways by different means. If ICT4D’s to be successful, we need to analyse that evidence base much more robustly.

The third’s the integration of ICT4D with broader development strategies – not just in terms of SDGs, but at national and local levels too. There’s no simple correlation between ICTs and economic growth, but a complex web of interactions that depends on national as well as global variables. Likewise ICTs and social welfare; poverty reduction; capabilities; gender equity. If ICT4D’s to be successful, strategies for ICT need to be immersed within national development strategies.

Less rhetoric, more evidence, more serious strategic thinking. I’ll return to these themes in coming weeks.

In next week’s blog, I’ll look at the challenge of measuring the impact of ICT4D.

David Souter is a longstanding associate of

David Souter is a longstanding associate of